The fact that the IPCC incorporates in its core business risks of failure to the Earth system and to human civilisation that we would not accept in our own lives raises fundamental questions about the efficacy of the whole IPCC project. If low risks of failure are taken as a starting point, “net zero 2050” becomes not a soundly based policy aim, but an appalling gamble with existential risk.

by David Spratt, first published at Pearls&Irritations

The IPCC last week published a 36-page summary of its forthcoming AR6 Synthesis Report, which also comprises an 85-page longer summary, as well as a yet-to-be-published full volume prepared by physical and social scientists. All are based on the contents of the three main IPCC reports from 2021-22 — on the physical basis, impacts and adaptation, and mitigation — and three special reports on 1.5°C, on climate change and land, and the ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate.

The short versions are known as a Summary for Policymakers (SPMs) and are subject to political vetting. In this most recent instance, amongst many examples, Saudi Arabia vetoed a proposal saying that burning fossil fuels was the main cause of human-caused climate warming, despite the overwhelming evidence. Truthfulness was no defence in a room of climate diplomats.

There is a long history of such interventions, so whereas the long or full IPCC reports of research findings are written by scientists, the SPMs are voted and vetoed line-by-line by political delegates appointed by the 195 nations which comprise the IPCC.

As examples, in the IPCC’s first assessment report SPM (1990), the United States, Saudi and Russian delegations acted in “watering down the sense of the alarm in the wording, beefing up the aura of uncertainty”. In 2007, Prof. Martin Parry reported that: “Governments don’t like numbers, so some numbers were brushed out of it”. And in 2014 for the fifth report, SPMs on climate impacts and mitigation “were significantly ‘diluted’ under political pressure from some of the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitters, including Saudi Arabia, China, Brazil and the United States”.

Only one observer organisation was allowed to report on the most recent meeting to finalise the SPM. Ajit Niranjan gives a blow-by-blow account of the political acrobatics around almost every paragraph. For example: “Finland noted the root cause of climate change is the use of fossil fuels. Saudi Arabia strongly opposed inclusion of the sentence”; and “China tried to cut the most powerful finding from the report — carbon pollution must drop two-thirds in 12 years to keep global warming to 1.5 degrees celsius — but said it would be happy to keep the numbers in a table”. And so it went, with politically-appointed delegates deciding and deleting and amending what was considered relevant to policy-makers — that is, to themselves — in a self-referential loop.

Politics of the IPCC

In a recent commentary at The Conversation, Prof Nerilie Abram wrote that:

“A key aspect of IPCC [SPM] reports is that they are co-produced between scientists and governments. The summary of each report is negotiated and approved line by line, with consensus from all of the IPCC member governments. This process ensures the reports remain true to the underlying scientific evidence, but also pull out the key information governments need” (emphasis added).

The question is what do governments need, what do they want, and what do they not want?

And the problem is not just SPMs, but the wider process. The top decision-making level of the IPCC comprises government-appointed delegates/diplomats from the 195 member states. It is they who make the big decisions and most importantly elect a bureau of scientists for the duration of an assessment cycle, who in turn select experts to prepare the IPCC reports. To be clear, that top level of coordinating authors are political appointees, a process which has been underexplored in critical literature.

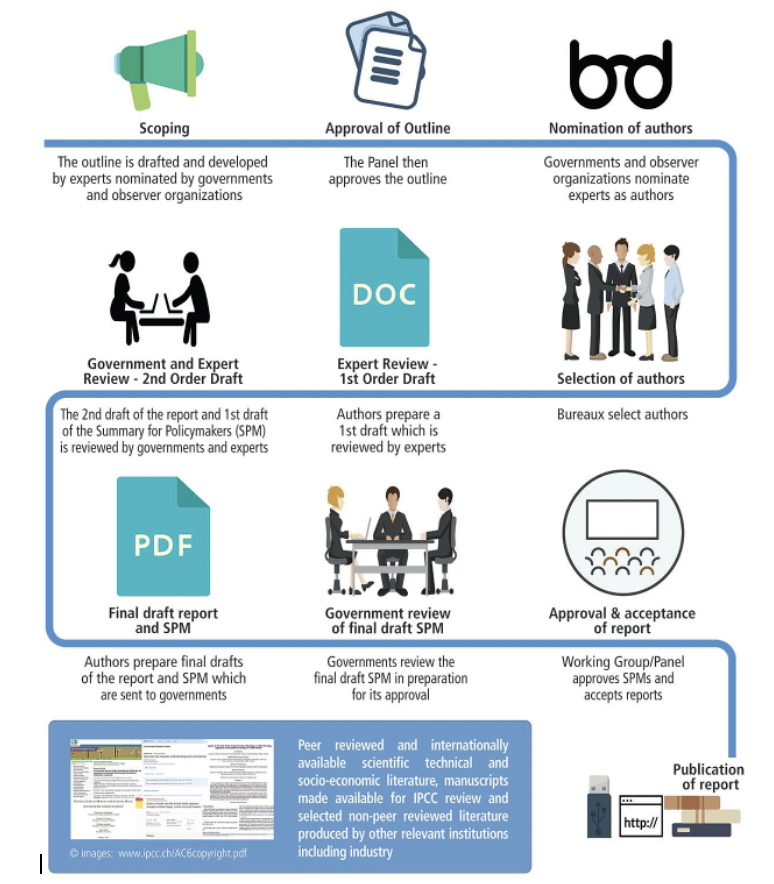

The lead authors then coordinate the drafting of the full report with input from thousands of scientists in a lengthy process. Their draft is reviewed by experts, but a second draft plus a draft SPM are then reviewed by governments. Governments again review the final draft SPM, as described above, in a process where any one nation has the power to delete anything it does not like. This whole process, as illustrated by the IPCC (below), is an essentially political process from the top, at the start and in the end.

|

| Preparation of IPCC reports https://www.ipcc.ch/about/preparingreports |

There is significant literature on how the politics of the IPCC works, and its conservative bias. As just one example, Michael Thomas reported that in the recent IPCC special report on land, authors wanted to recommend a shift to plant-based diets, especially in wealthy countries where meat and dairy consumption is so high. But environmental impacts of meat and the recommendation to shift to plant-based diets didn’t make it into the final report because delegates from Argentina and Brazil lobbied significantly for their removal.

Conservative science

The lead authors determine the shape of the scientific reports, and have the capacity to privilege certain methodologies and sideline others. A key feature of IPCC reports on the physical science has been to elevate climate models to the centre of the process, whilst relegating the bigger picture understandings that come from climate history (paleoclimatology) to a secondary position. Paleoclimatology teaches that in the long run each one degree of warming will raise the oceans by 10-20 metres. Models, unable to properly include cryosphere processes, suggest sea-rises to 2100 so small that the projections are not credible, a process of scientific reticence highlighted by NASA science chief James Hansen as far back as 2007.

Current climate models are not capturing all the risks, such as the stalling of the Gulf Stream, polar ice melt and the uptick in extreme weather events. Prof. Michael Mann says that “when it comes to certain important consequences of the warming, including ice sheet collapse, sea level rise, and the rise in extreme weather events, the [IPCC] reports in my view have been overly conservative, in substantial part because of processes that are imperfectly represented in the models.”

Another fundamental problem is the approach to risk. IPCC carbon budgets regularly include risks of failure (overshooting the target) of 33% or 50%, that is, a one-in-two or one-in-three risk of failure. Thus a 2-degree carbon budget with a 50% chance actually has a 10% risk of ending up with 4 degrees of warming, which is incompatible with the maintenance of human civilisation.

These are risks of failure that no government or person would agree to in any other aspect of life — whether it be buildings and bridges, safety fences or car seats — where acceptable failure rates are tiny fractions of one per cent. The fact that the IPCC incorporates in its core business risks of failure to the Earth system and to human civilisation that we would not accept in our own lives raises fundamental questions about the efficacy of the whole IPCC project.

If low risks of failure are taken as a starting point, then in an instance the so-called “carbon budgets” for 1.5 and 2 degrees reduce to zero. They cease to exist because they are an artifice of this appalling gamble with risk, and with them disappears any notion that “net zero 2050” is a soundly based policy aim.

This risk-management failure is incorporated into the heart of climate-energy-economy models, known as Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs) which are increasingly at the centre of IPCC economic and mitigation analysis, again peddling mythical carbon budgets. Yamina Saheb has provided a devastating critique of how highly-idealised IAM scenarios were selected for the Working Group III report of the current IPCC assessment.

Depending on how IAM modellers perceive the roots of the problem to be solved, they will “design the model structure, including possible instruments and relationships within the model accordingly… Hence, the very structure of a model depends on the modeller’s beliefs about the functioning of society”. Consequently, IAM results have the capacity to privilege particular pathways and entice policymakers into thinking that the forecasts the models generate have some kind of scientific legitimacy.

What the new IPCC says

Last week’s SPM report makes stronger statements than previous IPCC assessment summaries, but then again the situation is now much worse. Thousands of scientists have spent hundreds of thousands of hours developing the six full reports on which the SPM is based. Much of what was done is lost or downplayed in the SPM, though some strong messages survived, including that more than 3.3 to 3.6 billion people are living in places “highly vulnerable” to climate impacts and new extremes.

But there is a tendency to put into future tense what should be present tense. The SPM says that warming of more than 1.5 degrees would be devastating for Earth’s ecosystems and many people, but that is already the case because a number of crucial climate systems have already passed their tipping points at the current level of warming of 1.2 degrees. A search of key words relating to system tipping points and their consequences in the SPM is instructive: “feedback” appears once, “cascade” and “hothouse” not at all, “tipping” gets one mention, as does “Antarctic”.

There is no admission that limiting warming of 1.5 degrees is not a desirable outcome and would involve, amongst many outcomes, eventual sea-level rises measured in many metres and likely in the tens of metres.

And again, the SPM says that beyond the 1.5 degrees threshold, scientists have found that climate disasters will become so extreme that many people will not be able to adapt. But that is already happening. People are already fleeing from desertification of the dry subtropics, from unprecedented drought, and from the salination of their land, today.

In the report and the media commentary, there has been confusion about the feasibility of keeping warming below 1.5 degrees. Given the projected increases in emissions in the short term, which may not plateau till this decade’s end, and then remain high, the world is not within co-ee of keeping warming to 1.5 degrees (or even 2 degrees), and talk of 1.5 degrees is really about scenarios that involve significant overshoot and then trying to cool back to 1.5 degrees by century’s end.

Responses

The most interesting aspects of the SPM release was not so much what it said, but the commentary around it, most notably by the United Nations Secretary General António Guterres, who has long recognised the existential nature of climate risks and in February warned that rising seas threaten “mass exodus on a biblical scale”.

Presumably recognising that the SPM was not up to scratch, Guetrres went hard, saying the world was running out of options to defuse the “ticking climate time bomb” because “humanity is on thin ice, and that ice is melting fast”. His Acceleration Agenda, to be amplified by a UN Climate Ambition Summit in September in New York, calls on the world’s wealthy nations, including Australia, to sign a pact to reach net zero emissions 2040, to phase out coal power by 2030, and to block the extraction of any new oil or gas, a position far in advance of the SPM’s general tone.

Renew Economy reports that “It would also mean ending all international public and private funding of coal; ensuring net-zero electricity generation by 2035; ceasing all licensing or funding of new oil and gas; stopping any expansion of existing oil and gas reserves; shifting subsidies from fossil fuels to a just energy transition, and; phasing down existing oil and gas production compatible with the 2050 global net zero target.”

The Acceleration Agenda is a reminder to the Australian government that they are way behind where they should be.

A recent Australian study concluded that the IPCC is underselling climate change. “The accumulation of uncertainty across all elements of the climate-change complexity means that the IPCC tends to be conservative,” said co-author Professor Corey Bradshaw at Flinders University. “The certainty is in reality much higher than even the IPCC implies, and the threats are much worse.”

The SPMs are literally what they say there are: “summaries” of science for “policymakers”, arbitrated on by those same policymakers, and designed to be relevant to policymakers within the current policymaking paradigm, which has been mired in decades of failure. In those circumstances, separating the politics from the science is a complex equation.

David Spratt is Research Director of Breakthrough - National Centre for Climate Restoration

- Subscribe to the Climate Code Red email list for notifications of new posts