by Luke Taylor, first published at The Guardian

Philip Sutton, environmental activist; born 2 March 1951, died 13 June 2022

|

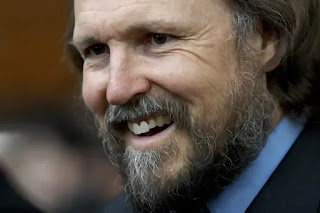

| Photo: Thom Rigney/Breakthrough |

Sutton’s work challenged the prevailing paradigm of a “reform as usual”, incremental-change strategy based on unclear goals. He campaigned on an understanding that climate risks threatened the future of the planet and of humanity, and therefore required a society-wide mobilisation at an emergency scale and speed. Sutton argued that getting into emergency mode rapidly was the central challenge for the climate movement.

This understanding was expounded in the 2008 book Climate Code Red: the Case for Emergency Action, written with David Spratt, which codified the term “climate emergency”, and shocked many readers into becoming climate activists. The book played a major role in shifting the narrative on the level of climate risk and our required response. Climate Code Red’s risk and impact assessments and climate system repair fundamentals have since been validated by mainstream analysis.

Sutton was at the forefront of environmental activism in Australia for more than 40 years. He was an assistant director of the Conservation Council of Victoria (now Environment Victoria) and worked as a councillor for the Australian Conservation Foundation from 1973 to 1976, and again from 2009 to 2015. In 1978 he co-authored Seeds for Change, a detailed alternative energy strategy for Victoria.

His influence and associations extended across a wide range of innovative environmental and climate organisations including Breakthrough – National Centre for Climate Restoration, Beyond Zero Emissions, Council and Community Action in the Climate Emergency, Sustainable Living Foundation, the Australia New Zealand Society for Ecological Economics and many more.

He was an initiating member of the movement that led Darebin city council in Melbourne to become the first local council in the world to declare a climate emergency, and played a leading role in the international campaign that has resulted in more than 1,000 local, regional and national governments to follow suit.

Sutton emphasised the need for climate strategy to be based on a clear, if discomforting analysis of the physical evidence of climate change, and for an approach to risk no less rigorous than those applied in areas such as engineering and aviation. He railed against the 2C “safe-warming limit” adopted by most climate advocates and institutions. Such a result would amount to “a death sentence for billions of people and millions of species”, Sutton argued.

Normalising goal setting based on the protection of “all people, all species and all generations” or “maximum protection”, was a framework which he pursued with tireless dedication.

Sutton’s ability to synthesise big-picture thinking with attention to detail, as well as his personal enthusiasm and generosity, were remembered in many of the tributes paid after his death.

The Greens senator Janet Rice said Sutton was “an intellectual giant” whose “absolute passion and dedication for a safe climate was unparalleled”.

Paul Gilding, former chief executive of Greenpeace International, called Sutton a “groundbreaking thinker”, while Mark Ogge of the Australia Institute said he was “extraordinary, incredibly influential in focusing us on the urgency of climate change”.

The former Victorian Labor environment minister Gavin Jennings said Sutton’s death was “devastatingly sad”.

“Philip dedicated his life to mobilise citizens, institutions and government to take the urgent actions required to keep life on this planet.”

Philip Sutton was born in Sydney on 2 March 1951. The greatest influence on him in his early years was his mother, Fay, who became an environmental activist serving on the Australian Conservation Foundation’s Council for more than 30 years. His father, Ralph, was an officer in the Australian Army and, as a result of his role, the family moved around a lot until they settled in Sydney where, as a teenager, Philip attended Sydney Boys High. He studied veterinary science at the University of Sydney in the late 1960s, but abandoned his degree in order to pursue urban creek protection and other local environmental causes.

In his early career, Sutton initiated the campaign that led to the banning of nuclear power in Victoria in 1983. He was the architect of the groundbreaking Victorian Flora and Fauna Guarantee legislation passed in 1988, the first of its kind, which became the model for the revision of wildlife legislation around Australia. He also worked on the federal government’s endangered species advisory committee (1990-93), the Victorian government energy strategy (1982-83), the Victorian state conservation strategy (1983-84), and with the Victorian Office of the Environment to develop strategies for achieving a successful green economy (1991).

Sutton met his former partner, the conservationist Kathy Preece, in the late 1980s, and they worked together on leading environmental legislation. They had two sons, Daniel and Joey, and as a family delighted in spending time together and exploring the wonders and science of the natural world.

Sutton’s dogged yet warm, genuine and unpretentious nature won the respect of many he worked with, even while he put forward confronting realities.

The former Greens leader Christine Milne said: “I had enormous respect for his intellect, his commitment and his courage to keep on telling it how it is, no matter how much that made people feel uncomfortable.”

Sutton is survived by sons Daniel and Joey.